![]()

ยุครุ่งเรืองของธุรกิจสตาร์ทอัพด้านอาหารอาจจะจบลงไปตั้งแต่ก่อนจะมีโคโรนาไวรัสเสียด้วยซ้ำ

จะเห็นว่าแบรนด์สตาร์ทอัพอาหารและเครื่องดื่มกำลังไปได้สวย แต่ในด้านการลงทุนเพื่อสร้างรายได้หรือเปิดตัวธุรกิจสตาร์ทัพใหม่ของตัวเองดูจะเป็นความเสี่ยงสูงเกินไปและยิ่งด้วยตอนนี้มีการแพร่ระบาดของโรคโควิด 19 “การลงทุนสตาร์ทอัพอาจจะเป็นวิธีการผลาญเงินทุนที่ดูเข้าท่าที่สุดเหมือนกับการเดิมพันระยะสั้น” Julian Mellentin, Director of international consultancy New Nutrition Business (NNB) ผู้เชี่ยวชาญด้านอุตสาหกรรมอาหารกล่าว

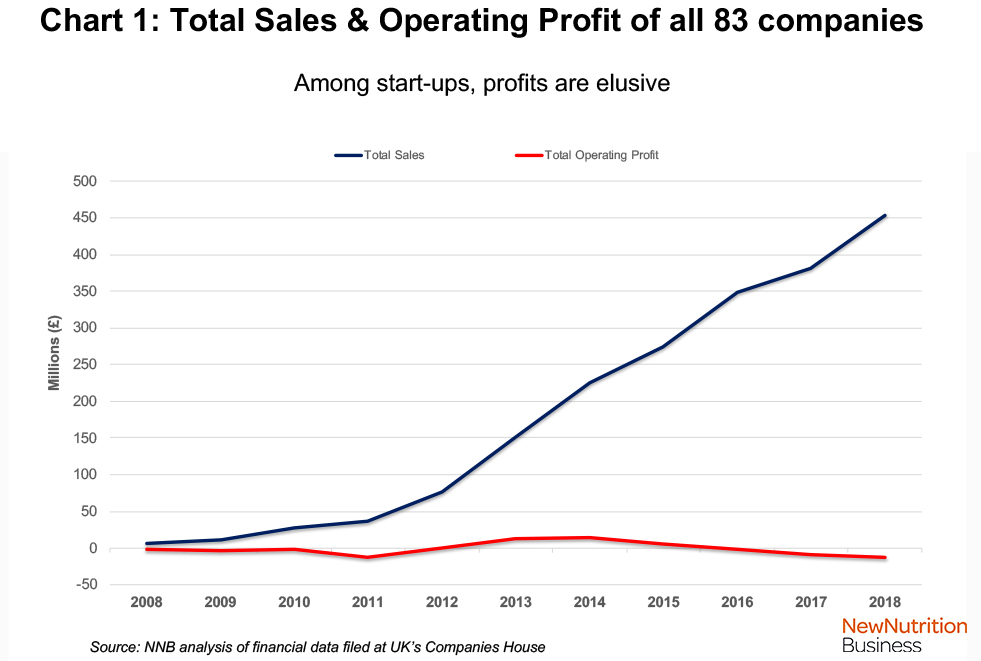

Start-up food and beverage brands are cool. But investing in, acquiring, or launching your own start-up is ultra high-risk – and even more so now thanks to COVID19. “A start-up may be the most effective way to destroy your capital, short of betting on horses,” says food industry expert Julian Mellentin, Director of international consultancy New Nutrition Business (NNB).

“In 2019 it was becoming clear that all was not rosy in the start-up garden,” said Mellentin. “We had learnt from talking to the market that most start-ups fail to achieve scale and most have terrible financials.”

“And the big successes that every investor wants – like Chobani or Grenade – were rare outliers,” he adds.

NNB’s research focused solely on the UK market, which is Europe’s start-up capital, producing more challenger brands than anywhere else in Europe. The UK retail environment also favours start-ups, with giant retailers willing to giving them shelf-space.

NNB selected 83 companies that had launched between 2005 and 2015. “We cut off at 2015 so that there would be at least three years of data for the newest companies,” Mellentin explains.

The analysis shows that achieving profitability and scale is the exception, not the rule:

• In 2018, only 27 (33%) of the 83 businesses made any profit. The combined sales of these profitable companies was £238.9 million ($298.4m/€273.5m).

• Of these, only seven achieved any scale.

• A further 15 (18%) folded.

• The remaining 41 (49%) were producing losses.

• Failure to scale = no profitability – the ‘happy place’ was found at annual sales above £35 million ($43.7m/€40.1m).

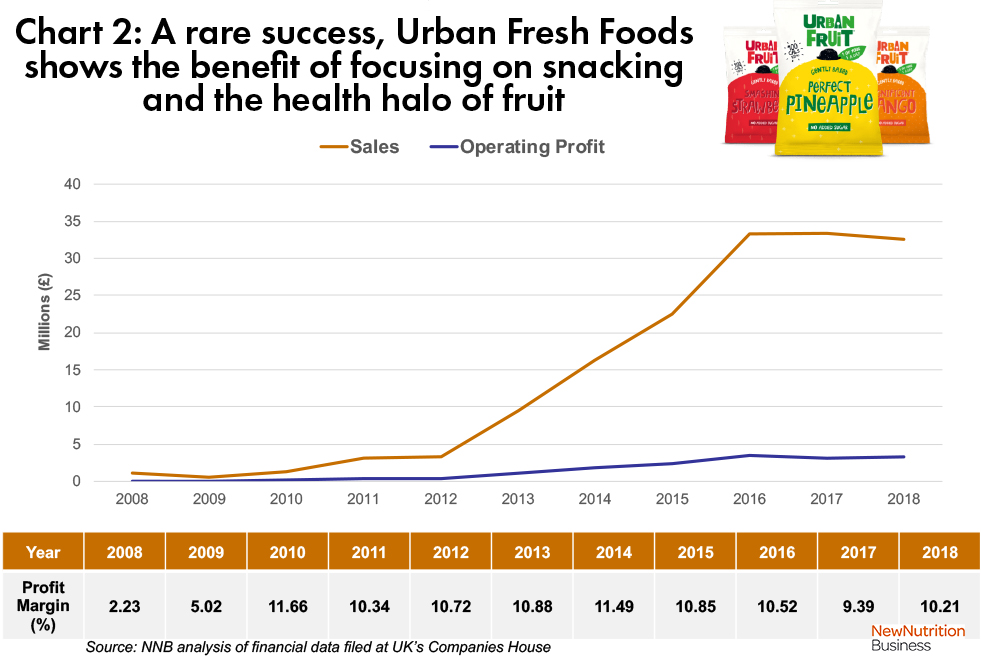

The biggest winners were in snacking

Snacking was the most profitable category with an average profit margin of 4.2%. The three most successful companies in the total sample were snacking companies:

1. Nature Delivered (better known by its Graze brand)

2. Grenade, maker of Carb Killa bars

3. Urban Fresh Foods, a maker of fruit snacks for kids and adults

These three companies alone accounted for 51% of the sales and 52% of the total profits of the 27 companies who were profitable in 2018.

Dairy did well, plant-based dairy did not

“The dairy companies in our sample were also mostly successful,” comments Mellentin. “Companies like Collective Dairy and Biotiful are growing and making profits.”

However, none of the companies making plant-based substitute milks or yoghurts in the sample had ever made a profit, and in one case losses were worsening each year: “Despite the hype about dairy substitutes, it’s clearly still a niche and a very crowded one.”

NNB’s research threw up a few golden rules for start-up success:

1. Understand the category you are going into: Know the category and its dynamics (and which categories to avoid). It’s clear that some categories have profound challenges. Gluten-free bakery, for example, may be past its peak.

2. Successful entrepreneurs don’t always win twice: Previous success is no guarantee of success with a new venture. It depends more on the category dynamics. “One very successful entrepreneur had gone into a new category, but after seven years the new business was still nowhere near making a profit,” says Mellentin.

3. Create a point of difference: Collective Dairy is a successful insurgent brand in the UK. Its flavours, packaging and total proposition stand out in an over-crowded yoghurt aisle.

4. Good taste and texture help you win: Grenade, Urban Fruit, Graze, Collective Dairy, Biotiful – all these companies deliver on taste and texture and they are among the biggest winners.

5. If you want to sell your business, make a profit: “The investor’s hope, which originated in Silicon Valley 20 years ago, is that you can focus on growth and the profits will follow,” Mellentin observes. “It’s clear that in food and beverage that doesn’t apply. None of the loss-making businesses achieved an exit sale for their founding investors, with the exception of one bakery business which was sold to a private equity group which has since grown sales but never managed to make their acquisition achieve a profit.”